JRPG’s are close to my heart. I grew up with them, like I’m sure a lot of folks did. Titles like Grandia, Final Fantasy 6, Chrono Trigger, the classics and obscure alike. Wordy RPG’s that were obtuse as Hell to get into for a kid who thought all this anime stuff was absolutely amazing. It also meant that I had to learn to read a lot faster than other kids my age.

As I got older and played more games, absorbed more media, and just generally learned more stuff and things, I learned about tropes and clichés. About the Heroes Journey and all that kind of essential structural junk we see every day. And the more you recognize it, the more things that riff on it are funny. Parodies can be really great, but they can also be pretty darn overplayed.

I think we all remember the entire internet around ‘the cake is a lie’ or ‘arrow to the knee’. Parody can be a double edged sword, where one edge of the sword is clever and funny and the other feels like you’ve lobotomized yourself after making the edge as blunt as possible by beating it against a rock for five hours. This is not a good analogy.

Exploring UNDERTALE

But it’s important one, because it helps set up what makes a good parody and deconstruction. UNDERTALE is probably the best example that comes to hand, and one everybody’s pretty familiar with. UNDERTALE told the story of a child who fell down into a bizarre universe and from here offers three styles of play.

The first time around, players are likely to play it as a straight, traditional turn based RPG with some quirks. Players might not realise the importance of Mercy and kill a few monsters by accident. But from here, there’s two options, and they both have a lot to say about the nature of the RPG.

The ‘genocide route’ is just that, where players kill every single character they come across without mercy. Playing the game this way is also the closest the player will ever come to a traditional RPG experience. There’s grinding, which rewards experience, which levels you up. There’s turn based battles in which you’re actively attacking another character. By following conventional RPG rules learned through playing years of RPGs, you would be setting yourself up to fail, to the point where all future run throughs of the game become tainted.

Following the rules of the game itself though shows a different side. It takes traditional RPG conventions, as well as ideas from other games (like the dating sim) and riffs on them while, most importantly, creating its own world and story that creates an emotional connection and investment in its players.

But importantly is what it means for gameplay. It mixes genres to create something new, and interestingly, if played through the ‘mercy’ route completely, plays nothing like a traditional turn based RPG at all. The closest it comes is having turns be involved, in that you have to wait your turn to select mercy, but at no point does the player cause damage. The bullet hell is the focus, and any personal stats (other than health, of course) are completely ignored given players will remain on level one.

Through a singular system two very separate paths are created that lead to very different outcomes depending on if the player plays it straight, or whether they give into the game and follow its lead and message. This leads me into talking about Moon: Remix RPG Adventure, one of several games UNDERTALE took heavy inspiration from.

Looking at the “anti-RPG”

Moon: Remix RPG Adventure was originally released in 1997 for PlayStation. The team behind it, Luv-De-Lic, was made up mostly from folks who had previously worked on other big RPG’s, including a few members of the team that worked on Super Mario RPG, which itself was an oddity in the then slowly emerging world of the JRPG.

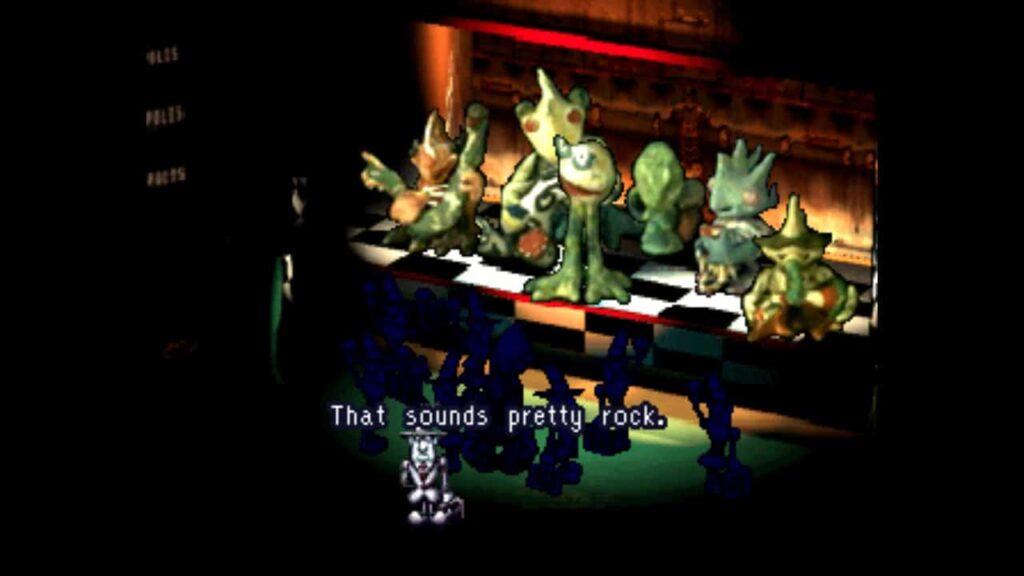

The game itself was billed as an “anti-RPG”, a parody and ‘remix’ of the growing popularity of the genre. It even drives home the fact in the opening scene, a boy playing his PlayStation, skipping the wall of text opening and playing the Hero through various portions of the game with goofy pixel graphics, characters with repeating and boring dialogue and encounters with monsters that may or may not actually be monstrous (but are certainly made to look that way).

The boy is then sucked into the game and the world suddenly goes from being boring and pixelated, to an absolutely gorgeous, hand-drawn looking environment with lush colours and characters with entire schedules and personalities, as opposed to the walking back and forth two dialogue worth of line characters we saw before.

Take, for example, the two guards at the palace. Moments ago they were identical sprites telling me to talk to the King. Now they’re both entirely separate people, one a divorced father desperate to fulfil a promise to his son, the other… Just a dude who loves jamming out to Freddy Mercury but only when no one’s watching.

Perhaps this is a celebration of the side quest, in part. The idea that a hero stops killing monsters for long enough to help some towns person just out of the goodness of their heart (and usually an item reward). The entirety of Moon is based around this, with every character having their place in the world and a trouble to be solved.

But unlike the traditional RPG, they won’t simply say ‘yeah I need this item can you get it’, instead the characters here are less likely to open up straight away and instead force players to learn about each individual and take the time to interact with and appreciate the world.

Let’s take our divorced dad, for example. Once a week, in the morning, he’ll go out onto the palace balcony to practice making and throwing toy planes. He promised his son that he’d manage to make one that flew for an entire hour. Through talking to him, and following him on certain nights when he goes to the bar, players can encourage him and help him achieve his goal, and in return, they gain love.

Love, in this game, is experience, essentially. The more love you have, the more you level up. Gaining levels, though, is what allows players to spend time in the world. On first opening the game, I had no idea what to do, and I died very quickly. The game is essentially on a timer, with love/experience being what increases that timer, and sleeping until the next day being what resets it.

Love is essential. But more than that, it really is the opposite of an RPG, where a player learns to love and care about a world through violent actions, here a player instead learns to love and care about a world through helping it thrive. Really understanding everyone in the world, right down to its monsters. Each monster is treated as a different kind of animal with its own quirks. In gameplay this is just a puzzle to figure out how to capture it, but in reality it’s just another way the game is forcing the player to understand the world in order to save it, rather than to brute force their way through.

Every part of the game is designed to reflect a living, breathing world that’s on the inside of any Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest, essentially. And to hammer home the point, the Hero is constantly just ahead of you, leaving death and misery in their wake but without even realising what they’re doing. And yet, strangely, it’s also barely touched upon. Perhaps because out of all the characters, the Hero is the least interesting, though they’re also the hardest to ultimately understand, besides some spoilery tragic context behind who they are and what they’re doing.

It’s all nothing new, especially now, but remembering this was 1997 and still holds up today as an absolutely impeccable, funny and quirky look at the JRPG genre and perhaps the nature of how we approach games as a whole, it’s still really darn good. Maybe it’s less of an ‘anti-RPG’ and more of an ‘open world kindness simulator’, or something.